TORTURE

In 1777, the country was roaring, and thinkers like Beccaria or Jean-Pierre Brissot were questioning the police as well as the judiciary system, whose inefficiency had especially been exposed during the Calas’ case in 1761. Because he was a Protestant, Jean Calas was blamed for the supposed murder of his own son—who, in fact, had committed suicide—, and executed. Voltaire used the public opinion to pressure the judiciary system, and eventually proved him innocent. This story had caused a stir in the kingdom, and when Cailleau insists on Desrues being guilty in his book, he mocks his claim of being “another Calas”. The question, or torture, had also become of great concern. It was denounced as inefficient and cruel, and was gradually abolished from 1780 to 1790. Not to mention the death penalty, and the way it was administrated. Indeed, the dreadful ordeal suffered by Damiens in 1757, after he had attempted to kill the King, had left a vivid memory. Did Lenoir fear that Desrues might become a martyr? “In France, people do not obey,” states Annie Duprat. “Those who dared defying the unfair system like Desrues, Cartouche or Mandrin, were seen as lovable rascals by those who suffered under the yoke of the Ancien Régime.”

Lenoir was walking on thin ice, aware that Paris had become a volatile city. First, Cailleau reminds the readers that Desrues could have avoided torture: “As he was prepared, Desrues was informed that he could be spared this torment should he confess his crimes. (...) He repeated that he had nothing to say.” Then, he claims that the public was satisfied with Desrues’ fate: “Some rounds of applause were allegedly heard during Desrues’ execution,” reads Vie privée et criminelle... “It must come as no surprise to sensible people, since we shall regard the passing of such a monster as a blessing.”

But is this book reliable? Public executions were some sort of pagan feasts, indeed, and most people attended to have fun, or to be part of an important social happening; “but let’s also bear in mind that three rows of armed soldiers surrounded the stake during each execution,” underlines Annie Duprat. “Which means that the mob could be hostile! Nothing proves that discontent was expressed during Desrues’ execution, but I would say that it was most likely the case.” To justify his execution, the police needed to establish Desrues’ guilt beyond any doubt—hence his 6-page long confession in Vie privée et criminelle..., maybe? Or the publication, in 1777, of his “true confession”, advertised by the publisher as being “written in his own hand”, and “found in his cell after he was executed” (Amsterdam).

Justice and propaganda

Cailleau gives a moving description of the villain on his way to the scaffold. He faced death with dignity, allegedly climbing the stairs—in fact, he was unable to walk, having suffered the torture of the brodequins, like Cartouche, which consisted in crushing one’s legs—like “an oppressed wise”, embracing his executioner, and had a kind of grandeur that impressed the witnesses. As he recognized a woman in the mob, he bowed to her: “Adieu, Madame.” She later confessed that “she had never found him more handsome and pleasant than at this precise moment.”

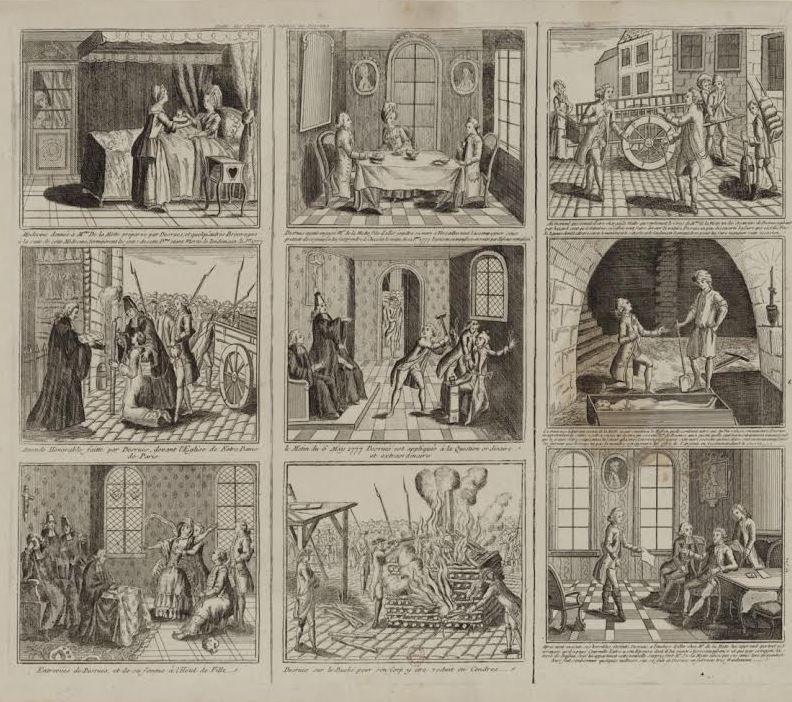

The engravings also give a rather flattering image of Desrues. “These images prove quite ambivalent, as they depict a poor man dressed as a good father,” notes Annie Duprat. If the aim was to darken Desrues, why did the publisher insist so much on this “grandeur d’âme” in the text? Annie Duprat wonders: “There is something sacred in the death of a man, I guess; that had to be rendered even in those books.” Maybe because these books were simply trying to attract the readers; be it by darkening the soul of the murderer or exaggerating his sorrowful execution.

The authors also got their information from the police. The printers, especially in matters of criminality, worked hand in hand with the police. Indeed, Vie de Nivet..., (Guyon, 1729), the life of another villain (see below), praises the crucial work of “M. Herault, Lieutenant de police” in the introduction, without whom “monsters like the one I’m about to tell would soon destroy the country.” The printers had no choice; it was Herault who gave the authorization to print and distribute Vie de Nivet... On the other hand, Vie privée et criminelle... reads: “The body of this villain had hardly been reduced to ashes that a legion of “gagne-deniers” (penny-earners) rushed the stake to collect his bones. Can we imagine people credulous enough to believe that the remains of such a man can bring them luck?” A popular belief that does not fit with the idea of a raging mob ready to swarm poor Desrues’ stake.

Conclusion

If Lenoir ever ordered these publications, he created a monster out of a monster. “Cartouche, Nives, Raffiat or Chabert, all these dreadful criminals, the dishonor of mankind, who perished under the hands of the executioners, had never shown as much atrocity in their misdeeds as Desrues,” reads Vie privée et criminelle... Was Cartouche a lesser villain than Desrues? He who was the alleged gang leader of 500 villains in Paris, he who had once opened the belly of an enemy and stuck his testicles in his mouth? Anyway, Annie Duprat confesses that, apart from Cartouche, none of the above names rings a bell. Nives is probably Nivet, as Thomas Thorpe lists a book entitled La Vie de Nivet, said Fanfaron, with the robberies and murders he committed from childhood (...) and who was broken alive at Place de Grève (Rouen, 1753). But this is one of the rare—and short, the first edition given in Paris (Nyon, 1729) being 46-page long—traces he left in history.

As far as Raffiat is concerned, he was a powerful gang leader around 1750. How come, then, Desrues became such a notorious villain despite his petty criminal records? According to A. Fouquier, “the reason why he inspired so much disgust and terror and that he is placed above all criminals, (...) is his impressive self-control.” Desrues was a very insignificant man, being small and quite weak—but behind this appearance hid a cold-blooded murderer who, up to the end, kept on denying his responsibility in Madame Lamotte’s death—he “stuck to wickedness,” to quote the cheap epitaph of La Vie privée et criminelle... Not even his imminent death could bring him a Christian feeling of remorse. His fortitude, far from giving a good image of him, probably contributed in forging his image of a man without emotion—in other words, a monster. In his famous Tableau de Paris (Neuchâtel, 1781), Louis-Sébastien Mercier writes about Place de Grève: “Herecame all those who thought they were untouchable; Cartouche, Ravaillac, Nivet, Damiens, and the worst of them all, Desrues. He there displayed the cold intrepidity and the courage brought by hypocrisy.”

If Desrues’ wax statue remained one of the main attractions of the Wax Museum of Palais Royal for years, as stated, how come he totally disappeared afterwards? Probably because Chaudon and Dandeline were right: petty criminals hardly enter posterity, unless revived by some book or some movie—like Cartouche. Far from the issues of the Ancien Régime and the Révolution, Desrues’ story slowly vanished. Only a few chipped books—and some very hard to find engravings—keep telling of his sad and violent life. On the naive frontispiece of a peddling edition of his life (Lille, chez Henry—early 19th century), one can confusedly feel all the darkness of his life; as well as the romantic dimension of his fate. In 1792, the revolutionists feared a plot and rushed the prisons to slaughter some 1,300 prisoners during the historical Massacres de septembre. Desrues’ wife, who had been sentenced in 1777, was among the victims—the last appointment of the Desrues with history.

Thibault Ehrengardt

![<b>Christie’s, Explore now: The Holkham Hebrew Bible.</b> In Hebrew, decorated manuscript on vellum [Toledo, 2nd quarter 13th century]. £1,500,000–3,000,000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9c82a169-2f34-4452-84ca-9e30c690769c.png)

![<b>Christie’s, Explore now: The Crosby-Schøyen Codex.</b> In Coptic, manuscript on papyrus [Upper Egypt, middle 3rd century / 4th century]. £2,000,000–3,000,000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/650de650-8a39-4eec-999a-6374a92124d7.png)

![<b>Christie’s, Explore now: The Geraardsbergen Bible.</b> In Latin, illuminated manuscript on vellum [Southern Netherlands, late 12th century]. £700,000–1,000,000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/ed5cc6d5-e2af-4910-83f9-519fa9dd18e4.png)

![<b>Christie’s, Explore now : Jean de Courcy (fl. 1420).</b> <i>The Chronique de la Bouquechardiere.</i> In French, illuminated manuscript on vellum [Paris, c.1480]. £200,000–300,000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/b379b534-a74f-4934-9a17-e78c1a848be4.png)

![<b>Christie’s, Explore now: The ‘Catherine de Medici’ Hours.</b> In Latin and French, illuminated manuscript on vellum [Paris, c.1485]. £120,000–180,000](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/9c67a1d9-70f4-4abb-99ec-e00dd318d510.png)

![<b>Freeman’s | Hindman, June 7:</b> HOMANN, Johann Baptist, HOMANN HEIRS, and Georg Matthäus SEUTTER. [Composite Atlas]. [maps dated between 1728-1765]. $30,000 - $40,000.](https://ae-files.s3.amazonaws.com/AdvertisementPhotos/2cc6c798-2b50-4e56-8550-624072cdf1c1.jpg)